Introduction to the Silence of a Soul

This is the brief history of an interior life. It is the biography of Ismael Molinero Novillo, better known to the Spanish Catholic Action youths as Ismael de Tomelloso since death took him on May 5th, 1938 at the Saragossa Doctors’ Hospital. His was a “life” without the great events, brilliant anecdotes or outstanding deeds expected by today’s utilitarian, pragmatic mentality. Still, it behooves us to linger once in a while, even if only briefly, on small happenings and take note of them, particularly in our times when there seems to be no interest in them. Modest, unpretentious adventures of little note barely get any attention at all, particularly when they are small matters of silence and meditation, the pure work of God’s Grace and man’s generous, quiet, accepting, startled reaction. Any man’s. For example, those of Ismael Molinero Novillo.

Undoubtedly, Ismael’s is an unusual “case.” His biography fills just half a page. There’s no room to let one’s imagination soar in a land such as was Ismael’s, where imagination is the order of the day and the artist finds his inspiration by interrogating the mazelike landscape, its lore, its fantasies. Ismael de Tomelloso’s brief, none-too-visible life could be told in the time it takes to recite the Creed or for a peasant to chat with a neighbor about the hot weather in the land of the Shrine to Our Lady. Ismael didn’t think of keeping a diary or confiding his spiritual thoughts to a notebook. He was fighting at the front, and what he wrote were standard letters to his family: I am fine, Mother; don’t worry about me. Here we’re freezing. All my best to the family...

Market in the constitution square. Year 1920.

He was just a country boy. He came from a far-off, out-of-theway town. A town lost in the La Mancha expanse. An island in the vast plain. The town with its typical dwellings, its flocks, its vineyards, its broad sunlit streets, its recesses and projections, the Plaza, the Club, the Church... One fateful, gloomy day the terrible wind of hate began to blow, and the accusations began: Those on the other side of the square are enemies; don’t trust what they do or say; they attend the novenas, listen to the priests... and so forth. Those were bad times. Hate is an awful company that never says yes. Ismael was one more boy to whom one day (because God pretends to just bump into the humble hearts, the simple people) some boys his age such as Miguel and Pedro—bold and brave young fellows in those trying times—talked to him about the Church and about a happiness that he had never suspected could exist.

The boys had joined the recently founded Catholic Action

Youth Center, headed by Fr. Bernabé Huertas. Ismael, Miguel,

Pedro and the others said to him, you can come over to the Center

if you like. It will be worth your while, you know?—Who, me?—

Hey man, of course you. And he replied, All right then. Since then,

a light began to slowly make its way in that wide open landscape,

that vast plain that was Ismael’s soul. With time, the light began to

outline his thoughts and his intentions, and new poems, and much

happiness poured forth from deep within his being. He gave these

gifts to the poor, the elderly, to young children and lonely neighbors,

to the simple womenfolk who shopped at the dry goods store where

he worked.

The boys had joined the recently founded Catholic Action

Youth Center, headed by Fr. Bernabé Huertas. Ismael, Miguel,

Pedro and the others said to him, you can come over to the Center

if you like. It will be worth your while, you know?—Who, me?—

Hey man, of course you. And he replied, All right then. Since then,

a light began to slowly make its way in that wide open landscape,

that vast plain that was Ismael’s soul. With time, the light began to

outline his thoughts and his intentions, and new poems, and much

happiness poured forth from deep within his being. He gave these

gifts to the poor, the elderly, to young children and lonely neighbors,

to the simple womenfolk who shopped at the dry goods store where

he worked. . I am of God and for God, he would often say. Despite

the tense, heavy atmosphere that engulfed the town, he noticed in

himself an immense desire to make everyone happy: his parents,

his siblings at home, the people he crossed in the Plaza early in the

morning while on his way to work. He would slip into Church as

quietly as possible to pay a visit to the Holy Sacrament. I want to

be a life example, he’d often say.

. I am of God and for God, he would often say. Despite

the tense, heavy atmosphere that engulfed the town, he noticed in

himself an immense desire to make everyone happy: his parents,

his siblings at home, the people he crossed in the Plaza early in the

morning while on his way to work. He would slip into Church as

quietly as possible to pay a visit to the Holy Sacrament. I want to

be a life example, he’d often say.

The Church of the Assumption and Casino of san Francis in the beginning of the twentieth century.

The Church of the Assumption of Our Lady of Tomelloso.

At the Old People’s Home he was happy whenever, on Sundays

especially, he could strum the guitar and sing jotas [traditional Spanish dances] to entertain the institutionalized guests who were

old and homeless. He would read poetry, organize dances for them

or improvise skits. Often, while conversing with one of the Sisters

or with Fr. Bernabé, or Miguel or Pedro, he would open up and,

impulsive and naïve as he was, blurt out: I want to be good, but I

don’t know how. But yes, he did know. Ismael was naturally good.

Good like the air one breathes. Like someone who tells a joke or

something funny to make the sad guests smile because, you know,

those poor wretches...

At the Old People’s Home he was happy whenever, on Sundays

especially, he could strum the guitar and sing jotas [traditional Spanish dances] to entertain the institutionalized guests who were

old and homeless. He would read poetry, organize dances for them

or improvise skits. Often, while conversing with one of the Sisters

or with Fr. Bernabé, or Miguel or Pedro, he would open up and,

impulsive and naïve as he was, blurt out: I want to be good, but I

don’t know how. But yes, he did know. Ismael was naturally good.

Good like the air one breathes. Like someone who tells a joke or

something funny to make the sad guests smile because, you know,

those poor wretches...  I wish I could be a priest some day, he dreamt.

He had taken a Spiritual Exercises course at the Ciudad Real Seminary

and had become attached to the Father who led the exercises

and to the seminarians... He was so devoted to the Holy Sacrament

that whenever he could he would stand and gaze at the Tabernacle.

More than once he commented: I’d like to be a priest. Thanks to

the example Ismael gave with his life, other young men would be

encouraged, over time, to take up the vocation. As we know, the

Spirit of the Lord blows where it will and when He wills it. Our

boy would have made a great priest. He had the aptitude and the

talent, according to his biographers. And he had hope, an enthusiasm

that sprang from deep within his soul. In the final stretch of

his life, when his body was ravaged by tuberculosis, he confessed

to the chaplain who assisted him: Father, I feel very happy.—Perhaps

you’ll get well, the priest replied encouragingly.—I want nothing

from this world, the boy continued, If I die, I will belong all to

God. If I don’t, I want to be a priest. A good priest. Like the ones

who serve God for free.

I wish I could be a priest some day, he dreamt.

He had taken a Spiritual Exercises course at the Ciudad Real Seminary

and had become attached to the Father who led the exercises

and to the seminarians... He was so devoted to the Holy Sacrament

that whenever he could he would stand and gaze at the Tabernacle.

More than once he commented: I’d like to be a priest. Thanks to

the example Ismael gave with his life, other young men would be

encouraged, over time, to take up the vocation. As we know, the

Spirit of the Lord blows where it will and when He wills it. Our

boy would have made a great priest. He had the aptitude and the

talent, according to his biographers. And he had hope, an enthusiasm

that sprang from deep within his soul. In the final stretch of

his life, when his body was ravaged by tuberculosis, he confessed

to the chaplain who assisted him: Father, I feel very happy.—Perhaps

you’ll get well, the priest replied encouragingly.—I want nothing

from this world, the boy continued, If I die, I will belong all to

God. If I don’t, I want to be a priest. A good priest. Like the ones

who serve God for free.

Indeed, the life and death of Ismael de Tomelloso were a life and death lived “free.” A completely free offering to God. Given quietly. It is amazing how the seed of God’s grace that the Catholic Action youths from his town had sown in the heart of Ismael took root and grew. He easily allowed the Spirit to work in him, enveloping that work in modesty and silence. Somehow almost concealing it. We could say that silence was the one outstanding feature of Ismael’s spiritual experience. It is difficult to imagine how such a naturally outgoing, friendly young man who was bursting with life could find the willpower to face the lot he drew in life, which was to step aside and pass unnoticed from this world. Far from him the desire to lionize significant events or deeds worthy of public recognition and applause. During the war, especially from the time that he was forced to fight at the front until he delivered his life up to God in Saragossa, Ismael lived as if shrouded in a truly heroic self-effacement. There was never a time when he didn’t walk as if on tiptoes through the land of silence. Without attracting attention. Without anyone guessing the torrent of love that leaped inside him and flowed to God. “All of God and for God.” And “to be silent and to suffer.” Someone has said that silence is the deepest truth. It was singularly so for Ismael.

It is a truth that he had discovered almost unconsciously. Like praying. Like drawing laughter from the guests at the Old People’s Home. Like loving Our Lady. Like treating the customers at the store where he worked with tact and affection. When the ‘38 class, his own, was drafted on September 18th, 1937, and he had to march with his knapsack and bedroll to the Teruel front with his mates, he had been fairly warned: Tell no one what you think or what you feel, or about Catholic Action or church matters, or about the other kids, or the nuns... Therefore—he must have mused—we must keep quiet and pray; and help whenever we can, if the chance arises, or sing a song softly, for it’s precisely those who believe in God who sing. When the Battle of Alfambra erupted in early February 1938, he offered his silence to God in exchange for peace. It was wartime and he was so poor that he had nothing else to offer. And besides, why should one reveal one’s membership in Catholic Action? Even if they take you prisoner and you go to the other side and are finally free to talk, it is still better to keep quiet and go straight, almost without a sound, to God’s mansions.

The place known as “Masada de la Hoya del Monte”, where Ismael of Tomelloso was taken from the “battle of Alfambra”.

And this is what happened. Pierced by the agonizing pain of

the tuberculosis he had contracted during that terrible winter, after

the battle he was taken to a prisoners’ camp at Santa Eulalia and

later to San Juan de Mozarrifar  : How lucky, my God, to be finally

able to take Communion. He asked for it in a whisper, a plea as

soft as a petal! but as if it didn’t matter much to him. But the chaplain

probably forgot about it. For who could have known how much

the frail twenty-year old prisoner who was quickly reaching the

end of his life and whose eyes shone like the lamps of the Holy

Sacrament in church, wanted to be a saint. The Lord always amazes

us and has his ways to make anyone fall in love with Him. Ismael

Molinero Novillo delivered his soul to God on May 5th, 1938. On

his deathbed, his silence broke like a bottle of perfume. Everyone

around him: the chaplain, the nurses, the members of the Saragossa

Catholic Action, praised God and gave Him thanks. And

soon, the young people of Spain were putting words to the silent

testimony of Ismael de Tomelloso. Over time, minor histories can

turn out to be very eloquent.

: How lucky, my God, to be finally

able to take Communion. He asked for it in a whisper, a plea as

soft as a petal! but as if it didn’t matter much to him. But the chaplain

probably forgot about it. For who could have known how much

the frail twenty-year old prisoner who was quickly reaching the

end of his life and whose eyes shone like the lamps of the Holy

Sacrament in church, wanted to be a saint. The Lord always amazes

us and has his ways to make anyone fall in love with Him. Ismael

Molinero Novillo delivered his soul to God on May 5th, 1938. On

his deathbed, his silence broke like a bottle of perfume. Everyone

around him: the chaplain, the nurses, the members of the Saragossa

Catholic Action, praised God and gave Him thanks. And

soon, the young people of Spain were putting words to the silent

testimony of Ismael de Tomelloso. Over time, minor histories can

turn out to be very eloquent.

The old school of medicine of Zaragoza, Clinic hospital.

Men’s room in the General pathology section of the Clinic hospital.

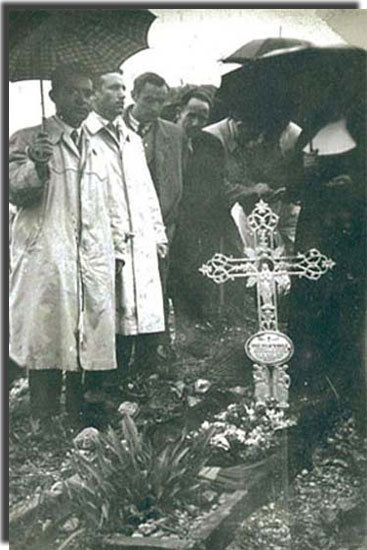

Grave in Torrero.

P. Valentín Arteaga

Postulador de la Causa de Canonización de Ismael de Tomelloso.